Re-Invent Democracy

with the Swiss-inspired

Direct Democracy Global Network

Video overview of the network is accessible here.

"We need AI to make democracy work for the 21st century."

"Rather than replace democracy with AI, we must instead use AI to reinvigorate democracy, making it more responsive, more deliberative and more worthy of public trust."

Eric Schmidt, former Google Chair and CEO

New York Times, November 11, 2025

Hello voters and activists eager to re-invent democracy!

By way of introduction, my name is N.J. Bordier. I'm the founder of the Direct Democracy Global Network now on the drawing board.

Its inspiration is two-fold: The first is Switzerland's centuries-old Direct Democracy in which Swiss citizens are politically sovereign. The second inspiration is world-renowned Geneva philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose treatises prescribed conditions for exercising popular sovereignty -- and preserving it.

As a political scientist, and citizen of the US and Switzerland, I've spent many years exploring pathways for blending the virtues of Switzerland's voter-controlled Direct Democracy with those of the US party-controlled political system.

The Direct Democracy Global Network attains this vital objective by incorporating decision-assisting AI technologies into an expanded 21st century repertory of Switzerland's voter-driven, consensus-building practices.

This combination makes it possible for voters across the spectrum to connect online to build consensus across partisan lines, and bridge the partisan divides that often stalemate the US system and many others throughout the world.

To achieve these objectives, the network provides voters a web-based, consensus-building space with unique decision-assisting tools and services.

Voters can access them free of charge 24/7 to collectively define and update their legislative priorities, set common legislative agendas, and devise compromises that bridge partisan divides.

The Direct Democracy Global Network is technologically capable of facilitating large-scale collaboration among voters around the world to build and manage online voting blocs, political parties, and electoral coalitions. Their members can reach across election districts, regions, and nation-states to elect representatives to set and enact voters' common legislative agendas.

Importantly, network tools enable voters to dialogue, debate, set priorities and legislative agendas through online votes, and implement life-saving common agendas, such as laws and policies halting life-threatening climate change.

Voters around the world can use the network to access an expanded 21st century repertory of Switzerland's unique direct democracy practices and tools. This repertory strengthens democratic electoral and legislative processes, by enhancing voters' roles in election cycles, legislative initiatives, referendums, and recall votes -- and possibly re-inventing 21st century forms of democracy.

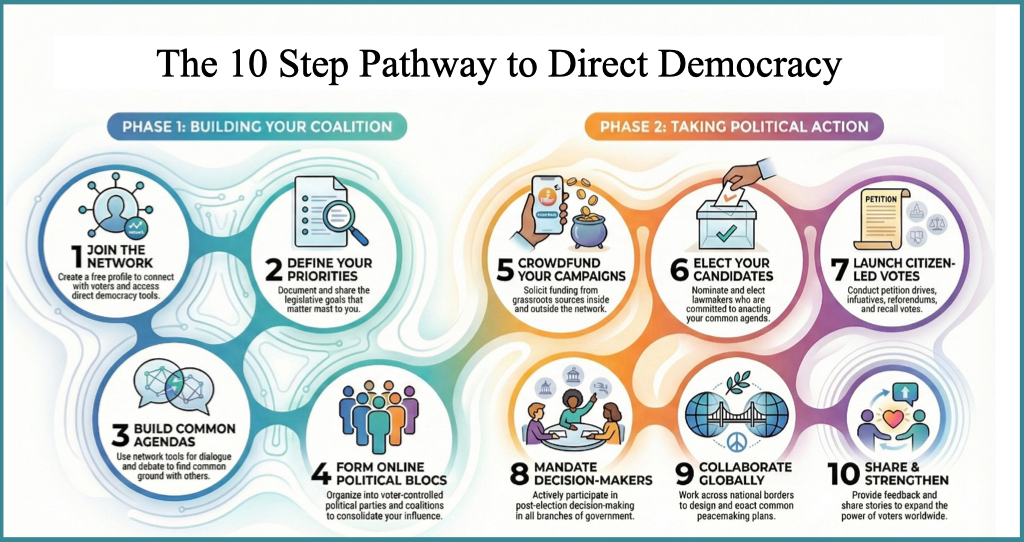

When fully operational, the network will connect voters around the world to collaborate online to accomplish the following:

- Describe and share individual legislative priorities and agendas.

- Reach out to voters. across the spectrum and nation-state frontiers, to build political consensus across partisan lines, through dialogue, debate, and voting on legislative priorities.

- Utilize objective, unifying AI technology to collectively set common legislative agendas, which cross partisan lines and bridge partisan divides.

- Join and democratically form and manage political parties, voting blocs, and electoral coalitions, online and offline.

- Nominate and elect candidates to enact consensus-based legislative agendas.

- Directly legislate by voting in network-conducted initiatives, referendums, and recall votes, and mandating lawmakers to exert best efforts to enact the results.

- Collaborate within and across nation-state boundaries to develop and implement domestic, regional, and global peace-making plans and policies.

What makes these great leaps forward possible is evidence and research demonstrating that consensus can be generated much more easily than ever thought possible -- especially by using emerging decision-assisting AI technologies that enable more people than ever before to define and share their priorities. and build consensus in support of shared priorities.

Recent multidisciplinary analyses indicate that consensus-building can be encouraged, facilitated, and expanded virtually everywhere, online and offline.

One successful research project was conducted by Professor Beau Sievers and his teams of researchers at Dartmouth College and Harvard University. Their findings demonstrate that settings can be devised that are conducive to consensus-building among diverse groups of people who did not previously know each other. (See "How consensus-building conversation changes our minds and aligns our brains". (2024))

"A few years ago, Dr. Sievers devised a study to improve understanding of how exactly a group of people achieves a consensus and how their individual brains change after such discussions."

"The results . . . showed that a robust conversation that results in consensus synchronizes the talkers’ brains — not only when thinking about the topic that was explicitly discussed, but related situations that were not.

"The study also revealed at least one factor that makes it harder to reach accord: a group member whose strident opinions drown out everyone else.”

“The groups with blowhards were less neurally aligned than were those with mediators."

"Perhaps more surprising, the mediators drove consensus not by pushing their own interpretations, but by encouraging others to take the stage and then adjusting their own beliefs — and brain patterns — to match the group. . . Being willing to change your own mind, then, seems key to getting everyone on the same page.”

Being able to change one's mind is characteristic of many more people than we are led to believe, as the result of the onslaught of "fake news" disseminated by social media. Research findings indicate that issue stances and legislative priorities of mainstream US voters tend towards “the center” of the political spectrum.

Their “centrist” views tend to diverge from those of partisan electoral candidates, incumbent lawmakers, political party activists, and donors, whose priorities tend towards the “right” and “left” of the political spectrum.

While the views of activists on extreme ends of this spectrum are more likely to be polarized, those of mainstream voters are not. This discrepancy dates back to the 1970’s, according to research conducted by Stanford University Professor Morris Fiorina, and published in Politicians more polarized than voters, Stanford political scientist finds.

I describe in the Ten Steps section below how voters can navigate the network, and what they can accomplish.

My concluding section describes Global Good News!

The Resources section provides more information about Switzerland's historic direct democracy form of government.

The steps described below enable voters to create multiparty political systems, which have long been considered indispensable to fully functioning democracies.

The advantages of multiparty systems are summarized by political party expert Lee Drutman as follows:

"Multiparty democracy with proportional representation is the norm among advanced industrial nations."

"Multiparty democracy provides fairer representation and generates more voter engagement."

"Multiparty democracy leads to more broadly legitimate, inclusive, and moderate policymaking."

"Multiparty democracy leads to more complex political thinking, more policy-focused and positive campaigning, and more compromise-oriented politics."

It is important to keep in mind the advantages of multiparty democracy emphasized by Drutman, when evaluating the unique potential of the Direct Democracy Global Network to enable voters worldwide to use Swiss-inspired direct democracy tools to create multiparty democracies.

Several decades of research demonstrating the value and efficacy of the phenomenon of crowdsourcing support key premises of the Direct Democracy Global Network, and the efficacy of the steps described below for tapping into its politically transformative potential.

They include the seminal work of New York University Professor Clay Shirky, who was among the first to recognize the unique potential of crowdsourcing initially demonstrated in the private sector,

He analyzed the web-based activities of self-selecting groups of people without previous organizational ties coming together to solve problems. Shirky’s prescient understanding of the combined power of these phenomena is described in Wikipedia as follows:

"In his book, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations., Shirky explains how he has long spoken in favor of crowdsourcing and collaborative efforts online. . . . He discusses the ways in which the action of a group adds up to something more than just aggregated individual action. . . The fourth and final step is collective action, which Shirky says is ‘mainly still in the future.’ The key point about collective action is that the fate of the group as a whole becomes important.""

Shirky's insights undergird Direct Democracy Global Network premise that voters -- especially dissatisfied voters -- are likely to use network tools to create and manage flexible online voting blocs, political parties, and electoral coalitions.

The members of these voter-controlled entities can use network tools and technologies, especially the voting utility, to build consensus and adopt, update, share, and publicize evolving priorities, while functioning democratically on an ad hoc and continuing basis. They do not have to wait until the approach of forthcoming elections.

Nor do they have to automatically transform their blocs, parties, and coalitions into formal organizations if they can operate effectively in their local environments without them. They can wait to decide to formalize their existence and operations until circumstances warrant -- e.g. if they wish to officially register their existence in specific election districts in order to obtain official ballot lines in chosen districts to run candidates of their choice.

Even then, these parties can choose to avoid replicating ideologies, agendas, and operations of traditional parties in existence for decades, which may not reflect the interests of contemporary voters at the grassroots.

In addition to Shirky’s contributions, the illuminating research and work of an American economist and Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom, PhD, lend empirical support to a core premise of the Direct Democracy Global Network that voters worldwide will use the network to autonomously self-organize.

In her path-breaking article, Are Ordinary People Able to Self-Organize? , she asserts that self-selecting groups of people are capable of governing themselves and their local communities.

Ostrom's extensive empirical fieldwork focused on how people interact with ecosystems such as forests, fisheries, and irrigation systems, challenging the conventional wisdom that ordinary people weren’t able to successfully manage natural resources without any regulation or privatization. She believed that people are perfectly capable of taking control of decisions that affect their lives.”

Applying her findings, "Ostrom described eight design principles that affect the success of self-organized governance systems, for example collective choices, mechanisms of conflict resolution, and the recognition of a community’s self-determination by the authorities.”

Applying Ostroms insights to crowdsourced blocs of self-selecting voters, they are likely to be motivated to tap into the Swiss-inspired direct democracy tools of the Direct Democracy Global Networkto exercise their political sovereignty to determine who runs for office, who gets elected, and what laws are passed.

These options and flexibility are inherent in the ten steps illustrated below.

Collective Intelligence and the Global Brain: Bridging Partisan Divides Worldwide

In 1982, British intellectual Peter Russell published an unusual book. He was a University of Cambridge graduate in theoretical physics, experimental psychology, and computer science, and his book was entitled The Global Brain. Few people at the time grasped the meaning of the book's title, or the future impact of the connections Russell foresaw between technology and people. I had the pleasure of meeting Russell at that time, but I did not realize how prophetic his concepts would prove to be.

Many years later, informed proponents of the global brain hypothesis assert the following:

"The Internet increasingly ties its users together into a single information processing system that functions as part of the collective nervous system of the planet"

"The global brain is a neuroscience-inspired and futurological vision of the planetary information and communications technology network that interconnects all humans and their technological artifacts. As this network stores ever more information, takes over ever more functions of coordination and communication from traditional organizations, and becomes increasingly intelligent, it increasingly plays the role of a brain for the planet Earth."

This is reassuring news in the face of increasing divisiveness and polarization that is preventing once robust democracies from taking actions needed to protect people's lives and ensure bright futures.

It is also reassuring that experts at prestigious academic institutions, such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), followed Russell’s conceptual lead and created organizations dedicated to taking advantage of the possibilities Russell described: "The MIT Center for Collective Intelligence explores how people and computers can be connected so that—collectively—they act more intelligently than any person, group, or computer has ever done before."

One of the Center's research scientists, Mark Klein, addresses cogently the challenges facing us:

"Humanity now finds itself faced with pressing and highly complex problems – such as climate change, the spread of disease, international and economic insecurity, and so on - that call upon us to deliberate together at unprecedented scale, incorporating the input of large numbers of experts and stakeholders in order to find and agree upon the best solutions to adopt."

"While the Internet now provides the cheap, capable, and ubiquitous communication infrastructure needed to enable crowd-scale deliberation, current technologies (i.e. social media tools such as email, forums, social networks, and so on) fare very poorly when applied to complex and contentious problems, producing toxic inefficient processes and highly sub-optimal outcomes."

On the personal front, I had the pleasure of getting to know Klein and his work years ago, which I found to be inspirational with respect to my own work in developing the Direct Democracy Global Network. I especially appreciate this statement of his goals:

"My research mission is to develop technology that helps large numbers of people work together more effectively to solve difficult real-world challenges. It seems that many of our most critical collective decisions have results (e.g. in terms of climate, economic prosperity, and social stability) that none of us individually want, suggesting that our current collective decision-making processes are deeply flawed. I'd like to contribute to fixing that problem."

"My approach in inherently multi-disciplinary, drawing from artificial intelligence, collective intelligence, data science, operations research, complex systems science, economics, management science, and human-computer interaction, amongst other fields."

Whew! I find it immensely encouraging that forward-looking members of the world's scientific community are focused on researching and resolving technologically the global challenges I've described in the preceding sections.

Truth-Telling-Technology and Large Scale consensus-building

Many of us are familiar with reports of the negative impact of social media misinformation that can be generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and biased and divisive algorithms. However, astute analysts, especially Oxford University's Polonski, dismiss this bad news and replace it with good news, by emphasizing the positive impact technology can and will play.

"It is easy to blame AI technology for the world’s wrongs (or for lost elections), but there’s the rub: the underlying technology is not inherently harmful in itself. The same algorithmic tools used to mislead, misinform and confuse can be repurposed to support democracy and increase civic engagement. After all, human-centred AI in politics needs to work for the people with solutions that serve the electorate."

"There are many examples of how AI can enhance election campaigns in ethical ways. For example, we can program political bots to step in when people share articles that contain known misinformation. We can deploy micro-targeting campaigns that help to educate voters on a variety of political issues and enable them to make up their own minds. And most importantly, we can use AI to listen more carefully to what people have to say and make sure their voices are being clearly heard by their elected representatives."

Fortunately, the unbiased AI algorithms and fact-checking technology of the Direct Democracy Global Network is designed to enable voters to devise compromises and bridge partisan divides, especially those that cause legislative stalemates.

These findings enable me to conclude this essay on a positive note. They also encourage me to again draw attention to my own work and invention of political consensus-building technology, which have generated core premises of the Direct Democracy Global Network.

To summarize in closing, the network empowers voters to re-invent democracy by applying and adapting Swiss-inspired direct democracy tools to build consensus across partisan lines, within their home countries and cross-nationally. They can access the network free of charge and build large scale online voting blocs, political parties, and electoral coalitions with sufficient voting strength to defeat and replace unresponsive lawmakers.

Mainstream voters whose critical thinking capabilities and centrist-oriented political views remain unaffected by social media disinformation, can connect online 24//7 to build consensus across partisan lines.

Voters can create cross-partisan electoral majorities, and circumvent Minority Rule political parties, candidates, lawmakers and governments that enable partisan minorities to ignore and overrule popular majorities, and even prevent their emergence.

By joining the Direct Democracy Global Network when it becomes fully operational, they can apply lessons they have been learning for centuries: Voters hold the keys to the future. Yes, the best is yet to come!

Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA)

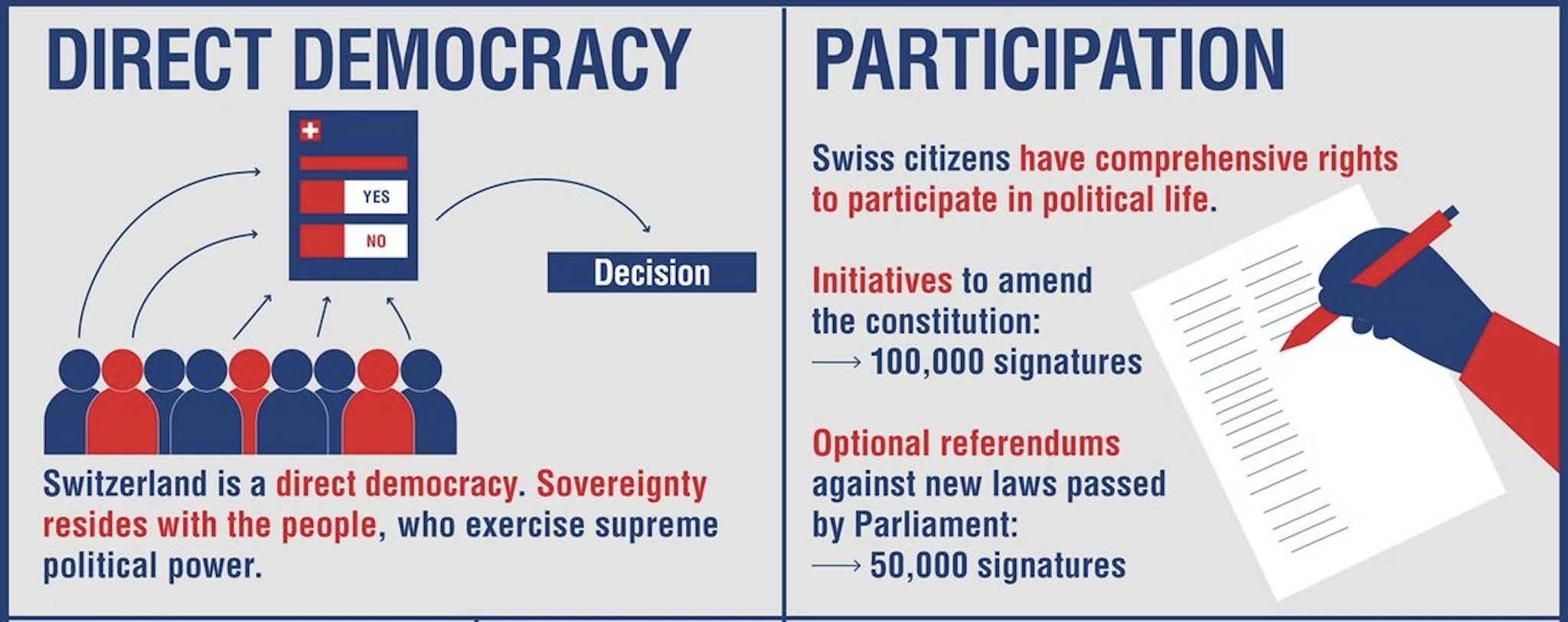

"Direct democracy is one of the special features of the Swiss political system. It allows the electorate to express their opinion on decisions taken by the Swiss Parliament and to propose amendments to the Federal Constitution. It is underpinned by two instruments: initiatives and referendums.

"In Switzerland the people play a large part in the decision-making process at all political levels. All Swiss citizens aged 18 and over have the right to vote in elections and on specific issues. The Swiss electorate are called on approximately four times a year to vote on an average of fifteen such issues.

"Citizens are also able to propose votes on specific issues themselves. This can be done via an initiative, an optional referendum, or a mandatory referendum. These three instruments form the core of direct democracy."

Popular initiative

"The popular initiative allows citizens to propose an amendment or addition to the Constitution. It acts to drive or relaunch political debate on a specific issue. For such an initiative to come about, the signatures of 100,000 voters who support the proposal must be collected within 18 months. The authorities sometimes respond to an initiative with a direct counter-proposal in the hope that a majority of the people and the cantons support that instead."

Optional referendum

"Federal acts and other enactments of the Federal Assembly are subject to optional referendums. These allow citizens to demand that approved bills are put to a nationwide vote. In order to bring about a national referendum, 50,000 valid signatures must be collected within 100 days of publication of the new legislation."

Mandatory referendum

"All constitutional amendments approved by Parliament are subject to a mandatory referendum, i.e. they must be put to a nationwide popular vote. The electorate are also required to approve Swiss membership of specific international organisations."

Swiss Confederation: Political System

"Switzerland is governed under a federal system at three levels: the Confederation, the cantons and the communes. Thanks to direct democracy, citizens can have their say directly on decisions at all political levels. This wide range of opportunities for democratic participation plays a vital role in a country as geographically, culturally and linguistically varied as Switzerland."

"Since becoming a federal state in 1848, Switzerland has expanded the opportunities it provides for democratic participation. Various instruments are used to include minorities as much as possible — a vital political feature in a country with a range of languages and cultures. The country’s federal structure keeps the political process as close as possible to Swiss citizens. Of the three levels, the communes are the closest to the people, and are granted as many powers as possible. Powers are delegated upwards to the cantons and the Confederation only when this is necessary."

Copyright © 2025 Re-Invent Democracy

All Rights Reserved