Welcome to the Direct Democracy Global Network

Roots of the Network

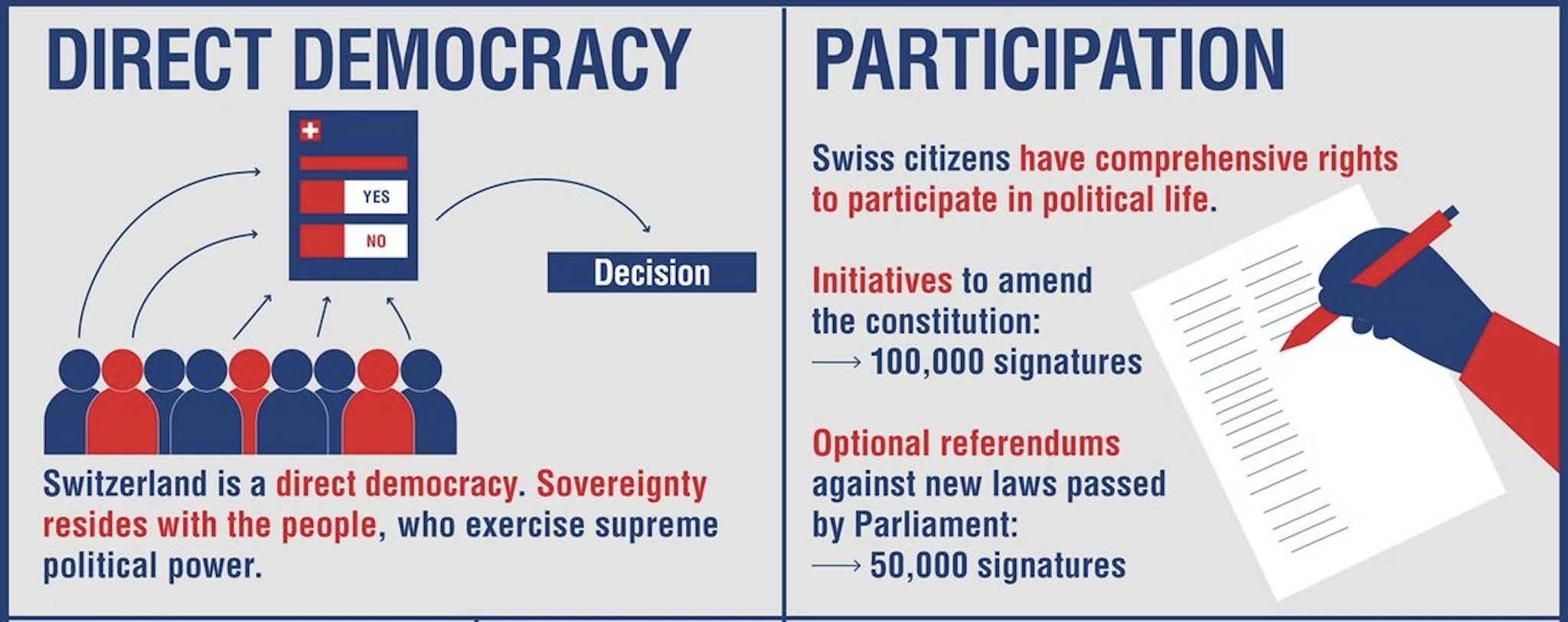

Switzerland's Direct Democracy in which Swiss citizens are politically sovereign.

Geneva's Jean-Jacques Rousseau whose treatises prescribed conditions for exercising political sovereignty -- and preserving it.

Purpose of the Network

Empowering voters worldwide to exercise their political sovereignty and determine who runs for office, who gets elected, and what laws are passed.

Ten Steps to Direct Democracy

The steps below describe how voters worldwide will be able to use historic Swiss direct democracy practices when the network is fully operational.

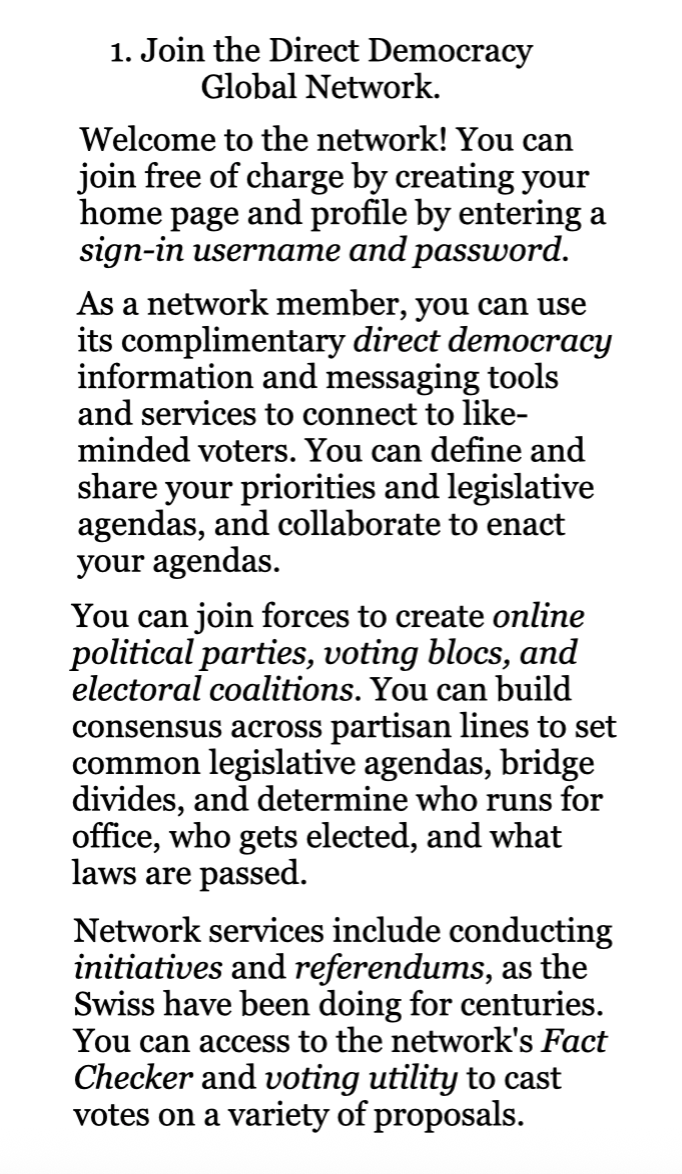

Step 1.

.png)

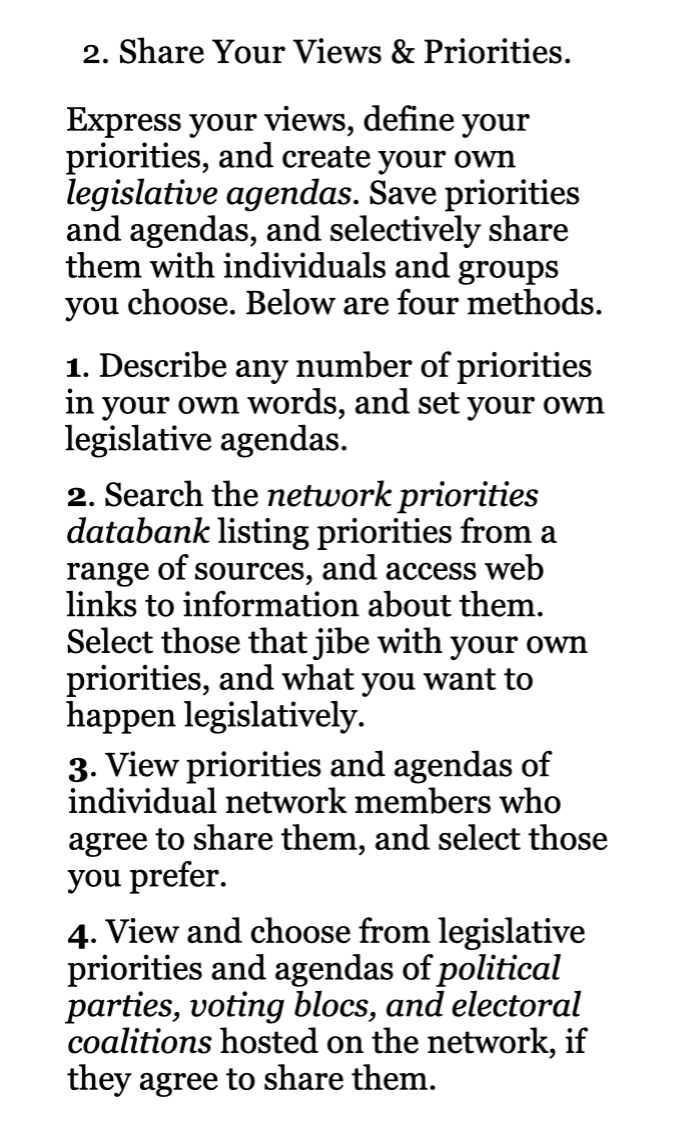

Step 2.

Step 3.

Step 4.

Step 5.

Step 6.

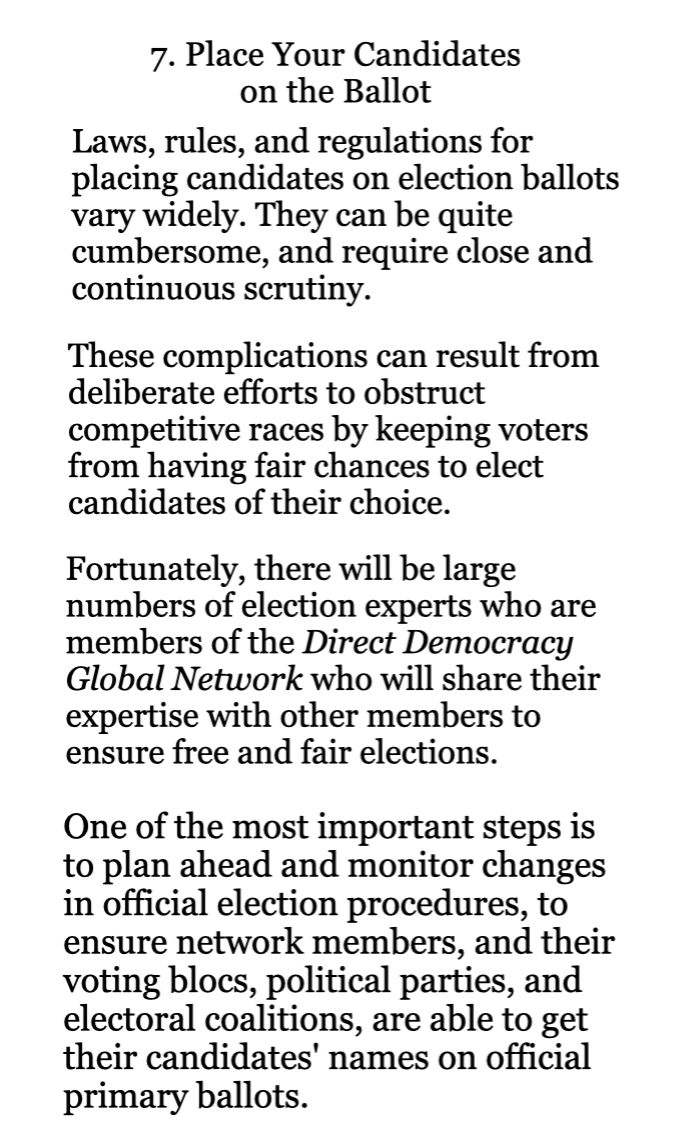

Step 7.

Step 8.

Step 9.

Step 10.

Kindly share comments and recommendations here:

info@ddgn.net

Copyright 2026 DDGN

All Rights Reserved